September 11 | 2020

Frequently in martial arts you hear laments about the changing nature of these arts and how particular styles were better years ago because they were more “traditional” or how they are better now because they are more “modern.” But rarely does anyone stop to ask just what constitutes traditional and modern in martial arts or where the dividing line is that separates any particular art into its traditional and modern phases.

Though some people would call karate as it’s currently practiced a traditional martial art, many older karateka will tell you it’s no longer truly traditional. They’ll argue that with the preponderance of newly made up kata, the focus on tournament competition and the blending of techniques from a variety of other martial arts, most karate just doesn’t qualify as a “traditional” art anymore. But that begs the question of “When was it a traditional martial art?”

Was the karate being practiced when it was first imported to Western countries in the 1950s and 1960s the traditional karate? Or was it the karate that was first imported to Japan by Gichin Funakoshi in the 1920s? Or does one have to go back to the time in the late 1800s when Funakoshi was learning karate in Okinawa to find the true, traditional karate?

Certainly whatever was being taught as karate in Okinawa, circa 1890, is a far cry from the karate that’s being taught in the United States in 2020. But at what point did karate go from being “traditional” to being “modern?”

The problem is, people tend to envision a radical break in martial arts between the traditional era and the modern era. An example of this comes in looking at the ancient martial arts of Japan, which are referred to as “koryu” or old school martial arts. These are generally regarded as the martial arts of the samurai class, as opposed to the “gendai budo” or new martial arts, such as kendo, judo and aikido, which all developed within the last 150 years.

It’s sometimes said that, to be considered a koryu style, a martial art must have existed before the Meiji Restoration ended Japanese feudalism in 1868. But does that mean if a Japanese martial art was created on December 31, 1867, it should be classified as a koryu while a similar martial art created on January 1, 1868 should be called a gendai budo?

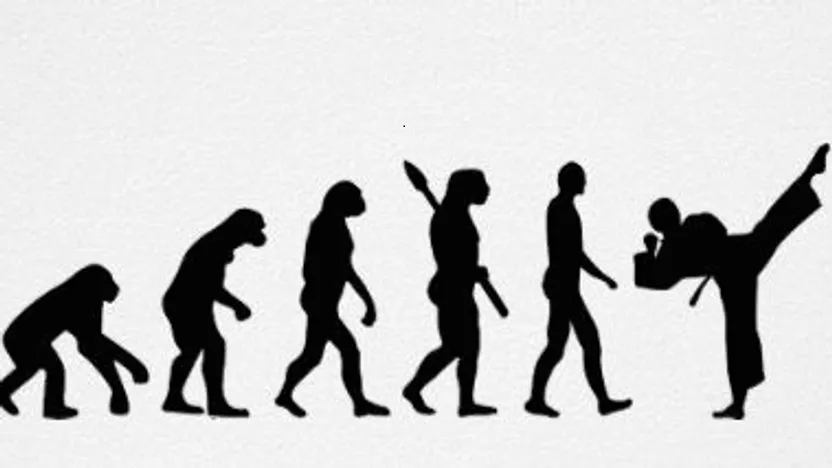

Clearly such a sharp delineation between old and new, between traditional and modern, is faulty. Yet this is how most people tend to view the contrast between what they think of as traditional and modern in martial arts. And while it’s true that if we examine karate in 1890 and 2020, we’ll see two almost completely different entities, there is no one point where this art underwent a revolutionary change. What we’re really dealing with is an evolution, not a revolution.

If you were to look at the karate of 1890 and, instead, compare it to the karate being done in 1900 you might see some changes but an art that was still essentially recognizable as what was being done in 1890. And if you were to look at karate in 1910, you would see something that had, perhaps, changed a bit more but was still fairly similar to what was being done back in 1900. There is no one year, or perhaps even no one decade, where you can look at karate and say it completely changed from one thing to another. Instead, only looking at it over a long enough period of time do we see changes so significant as to appear revolutionary.

So to call karate, or any other martial art that’s been around for a while, “modern” or to say it was once “traditional” is merely to summon up an arbitrary comparison to some idealized notion of an art that existed at an unspecified time in the past. Viewed in this manner, the terms “traditional” and “modern” lose most of their meaning in martial arts.

Put another way, there are no true “traditional” or “modern” martial arts. There are just martial arts.