December 09 | 2013

Nearly everyone knows the four ranges of combat: kicking, punching, trapping and grappling. In this story, a veteran jeet kune do instructor discusses his preferred ways for addressing three ranges you might not have thought about.

Nearly everyone has heard of the four ranges of combat: kicking, punching, trapping and grappling. They are perhaps most often associated with training in jeet kune do, in which students seek to acquire different skills from different arts to prepare themselves to fight in any situation. Yet there’s another set of ranges — only three this time — in JKD training. They are the high, middle and low ranges. If you train to strategically use them, you can transform yourself into a smarter fighter and your opponent into a blithering fool who gets taken out of commission more quickly, more easily and more efficiently.

Fight Smart

Physically, Bruce Lee was not a big man. At about 130 pounds, he had to make sure his techniques and strategies were the most efficient and realistic ones known. JKD-concepts instructor Ralph Bustamante is in the same boat.

“I’m at 150 pounds right now, and this is probably the heaviest I’ve ever weighed,” said Ralph Bustamante, who’s certified under Burton Richardson and has trained with Dan Inosanto, Richard Bustillo and the Machados. “For me to pull something off, I have to really get the technique down, but technique alone is not going to get me where I want to go.”

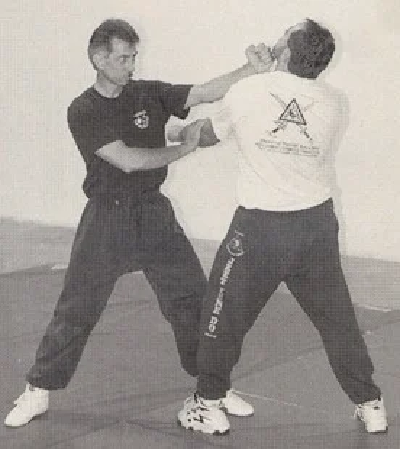

That’s where the three ranges come into play. The guiding strategy goes something like this: When your opponent attacks you in one range, that means he’s focusing all his attention on that range. Therefore, the logical choice for you is to counterattack him in a different range.

“When a person is doing something in one range, he’s forgetting about the others,” said Ralph Bustamante, who teaches JKD in Santa Clarita, California. “If you’re in trouble in a fight, you should address those ranges that he’s not thinking about.”

Definitions

In a confrontation, your opponent — even if he’s untrained — can easily attack you in any of the three ranges. Using the high range, he might throw a punch at your face. Using the middle range, he might throw a hook to your breadbasket or a knee to your sternum. Using the low range, he might launch a kick at your thigh or knee.

The key to using JKD’s three ranges lies in protecting the body part your opponent attacks by evading, intercepting or blocking, then counterattacking to a different range. Sounds simple, doesn’t it?

“It takes a little training to be able to use the ranges,” said Ralph Bustamante, who has trained in the martial arts for more than 30 years. “First, somebody has to tell you they exist. People with no experience don’t know they can attack a different range. It’s like they have a rule book that says what they can and cannot do in a fight. But constantly being exposed to the fact that you do have an alternative and training so you understand what that alternative is all about gives you an edge.”

Why don’t more martial artists know about — and use — the ranges? “A lot of people have been exposed to them, but they seem to push them to the side,” Ralph Bustamante said. “I think it’s because they want to crash heads — they want to compete with each other at the same level. That’s not the most advantageous way to do it unless you’re doing tournament fighting. On the street, you have to be ready to mix and confuse your opponent, and you can do that by addressing the different ranges.”

Denial

The average martial artist hopes — and trains — to defeat his opponent with whichever skills he knows best, Ralph Bustamante said. That can work well if your opponent is good at one range (say he’s a boxer) while you’re good at another (a skilled muay Thai thigh kicker, for example).

But what if you and your opponent happen to be good punchers? You could end up slugging it out in a no-rules boxing match. Unfortunately, this is often the product of conventional training, in which students spar with practitioners of the same style: Boxers box with boxers, taekwondo practitioners kick other taekwondo practitioners, etc.

Presenting an attacker with something he’s not used to and, therefore, not good at defending against, makes more sense. “I’ve dealt with some kickboxers who were good at what they do,” Ralph Bustamante said. “But when they try to deal with the different ranges, they’re thrown off. It takes them by surprise because it’s not in the range they’re familiar with.”

When the three ranges are used successfully, shocked martial artists are often filled with disbelief. “A lot of times, there is denial,” Ralph Bustamante said. “They can’t quite understand it. They want to try again, and generally they lose again because they’re not even competing on the same level.”

With a typical tournament match or mixed-martial arts fight, it’s relatively easy to determine your opponent’s style before you tangle with him. But on the street, how can you know? “You don’t ever really know what the person is going to do,” Ralph Bustamante said. “If he’s a street fighter, he could pick something up from the ground, and that throws everything out the door as far as wanting to go over and do some boxing with him. However, most will rush you and take you to the ground.” Others will try to punch your head. The best thing to do, Ralph Bustamante said, is stay away from your opponent and try to get an idea of how he fights.

As soon as you determine his style — that he’s a headhunter, for example — that’s your cue to go for his middle or low range. “The first thing you should think is, ‘What is he doing?’ because whatever he’s doing, you don’t want to do,” he said.

Continued in Fighting Ranges of Jeet Kune Do, Part 2.