Drilling will take you and your students a long way toward becoming better martial arts technicians, but it’s not all you need. The psychological guidelines presented here are essential to efficient learning.

How many side kicks have you performed? How many thousands of punches have you thrown? Why did you do so many? While simultaneously pursuing a master’s degree in clinical psychology and a black belt, I found psychology’s answers to many of my martial arts questions.

One reason for repeating a technique many times comes from physiological learning theories. When you perform a technique, a small electrical charge is conducted through your brain in a pattern particular to that activity. Each time you repeat the technique, the same pathway is followed.

Just as a trail in the woods becomes more defined with use, so will the electrical pathways in your brain. The more you practice a technique, the easier it is for electrochemical processes in your brain to repeat the pattern.

In short, your brain will perform the cognitive, or mental, portion of the technique more quickly; therefore, your body will be able to perform the physical portion of the technique more quickly and efficiently.

Another relevant psychological theory is that of behavioral conditioning. Behavioral theorists support the notion that physical practice leads to more efficient performance.

For instance, if you want to teach a student to stand his ground and counterattack an opponent, shouting for him to do so is not the most efficient teaching method. Instead, have him practice his counterattacks with you or a focus pad, and do so slowly at first. Reward successful efforts with verbal praise or by withholding push-ups, depending upon your style.

When the student is proficient at counterattacking at a snail’s pace, slowly increase the speed of your attack. He will increase his response skill and become more confident. Finally, practice continuously at full speed, intermittently rewarding him for his good work.

The payoff comes during sparring sessions when the student automatically counterattacks his opponent. The repeated practice conditions the student to instantly counter when he sees an attacker coming toward him. With enough practice, or conditioning, the technique becomes a reflex, bypassing conscious thought. At this point, the quickness and efficiency of the technique take an exponential jump, which is well worth the time spent practicing.

Social psychologists also have researched individual performance levels in pressure situations. They have found that a person’s performance can either improve or decline under pressure, depending on the complexity of the task being performed.

For instance, if a person is asked to wind a fishing reel as fast as he can, he will wind it more quickly under time pressure and in view of others than if he is alone in a room. If you ask the same person to solve math problems, however, his performance will decrease under the same pressures.

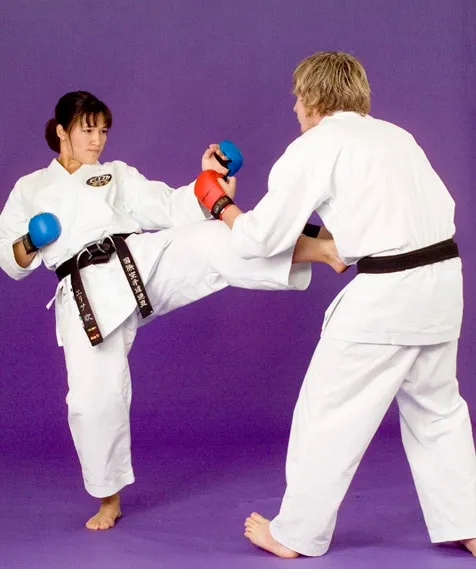

How can you use this information to aid your martial arts practice? The trick is to simplify the performance of complex tasks through repetitive practice. Clinical psychologists have found that black-belt students perform kicking drills more efficiently when they are being watched and graded, whereas colored-belt students perform less efficiently under the same conditions. Why? Because the black-belt students have practiced the technique so many times that it has become a simple task, whereas the drill remains complex for the colored-belt students.

The reason Larry Bird made a higher percentage of free throws in pressure situations is he had practiced the free throw so many thousands of times that it became a simple task for him. Others would choke in the same situation because a free throw is not an automatic, simple task for them.

A reverse punch, however, is something that you have practiced often enough that your performance should increase under pressure — whether fighting for points in a tournament or for real on the street.

This post has discussed from a psychological perspective several reasons why you need to continually practice your techniques. If those reasons are not enough to make you want to practice, do it so your instructor does not make you do more push-ups.

David F. Clark is a freelance writer and martial artist based in Vineyard, Utah.

Photos by Rick Hustead